Some say it’s a perennial pain in the ass. Attack it early and often to protect the sanctity of your yard.

I wouldn’t exactly call where I grew up in the twin cities charming. With the exception of a few nice parks and bike paths, it is your standard carbon copy of a copy of some generic dream of suburbia.

There is, however, something strangely comforting about hanging out at my parent’s house and watching other people potter about their lawns. They always move slowly — almost ritually, as if all the weed whackers and XXL pitchforks and miniature tools in the world are holy relics in an ageless war against opportunistic plants.

Our own front flower beds are pretty much 100% fern. And our yard is an enclave for every rogue plant imaginable: plaintain, violets, weird types of grass. I’m not sure my parents mind.

Which is perhaps for the best. Because violets don’t care about your hopes or dreams for pure, unadulterated bluegrass. They have zero shits to give. And large colonies will absolutely spread like small-town gossip throughout your yard.

Photo: Liz West / CC BY 2.0

But the curious thing about violets isn’t the rate at which they spread.

Instead, it’s how they do it: with seeds, underground networks of spindly rhizomes, and even super-secret, pale-white buds. Known as cleistogamous flowers, these secret beauties (named after the latin term for a closed or “self” marriage) can hide underground because they don’t need pollinators or even the sun to produce viable seeds.

They can pollinate themselves alone, even in the dark.

According to many gardening websites, a campaign of pesticide-fueled annihilation is your only hope of reducing a scourge such as this. Yet the leaves and flowers of violets are surprisingly edible; and not everyone views the appearance of a cluster of these tiny, purple beauties as an assault on common decency.

Photo: Rachel Kramer / CC BY 2.0

The botanist Eloise Butler (an early advocate for natural conservation and the protection of native plants) often and rather intentionally planted many varieties of violets in her gardens. She believed no other flower, save a red rose, was as beautiful. And while she most famously opened the Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden in Minneapolis in 1907 (which today remains the oldest wildflower garden in America) — she also wrote a regular column for the Minneapolis Star Tribune.

In 1911, she wrote that even a man “supposedly guiltless of dropping into poetry” could fall deeply, madly in love with the common blue violet. And she wasn’t the only one to wax romantic about the flower.

As early as 1620 lozenges known as violet tables were flavored with the fragrant, european cousin of the common blue violet (known as sweet violet). Violets have also been cooked or incorporated into a variety of sweets and candies, including flower pastries, sweet meats, and the infamous British parma violets; they have been included as thickening agents in soups; and during the Edwardian era, it was popular to infuse them into medicinal chocolates or liquor as a cure for nausea.

None of this seems to compare, however, to the feverish wonder that once existed for violet as a perfume, a bouquet, or even a simple posey. Napoleon famously wore violets as a symbol of his victorious return from exile — and violet posies even have cameos in some of the cherished, famous works of art and literature.

In Hamlet, Ophelia laments that she would have picked a posy of the purple flowers, but they “withered with the death of [her] father.” She drowns in a stream surrounded by flowers, a scene depicted in the Sir John Everett Millais painting, Ophelia.

Ophelia by Sir John Everett Millais, 1851. Photo: Tate, London, 2011

The Tate museum notes that each flower depicted was carefully chosen for symbolism, and that violets, “which Ophelia wears in a chain around her neck, stand for faithfulness, chastity, or death of the young, any of which meanings could apply here.”

Violets are also depicted in Ford Madox Brown’s painting, Convalescent, Portrait of the Artist’s Wife which, again, mourns the all-too-soon death of a woman.

In addition to fine art, the symbolic language of flowers also had a heyday in 19th century literary flower dictionaries for women. The content of each of these guides (such as Flora’s Dictionary, published in 1829) appears to have varied, based on scientific information, folklore, and sometimes purely arbitrary nonsense. But it also invariably was based on the traditional roles and virtues expected of women in America and abroad.

As scholar Corinne Kopcik Rhyner notes in her dissertation, “Flowers of Rhetoric,” on the prevalence of the language of flowers in 19th century American literature, “In America the language of flowers was a popular phenomenon […] traditionally associated with True Womanhood ideals for women to be pious, pure, domestic, and submissive to their husbands.”

I just barfed. But not all is lost —

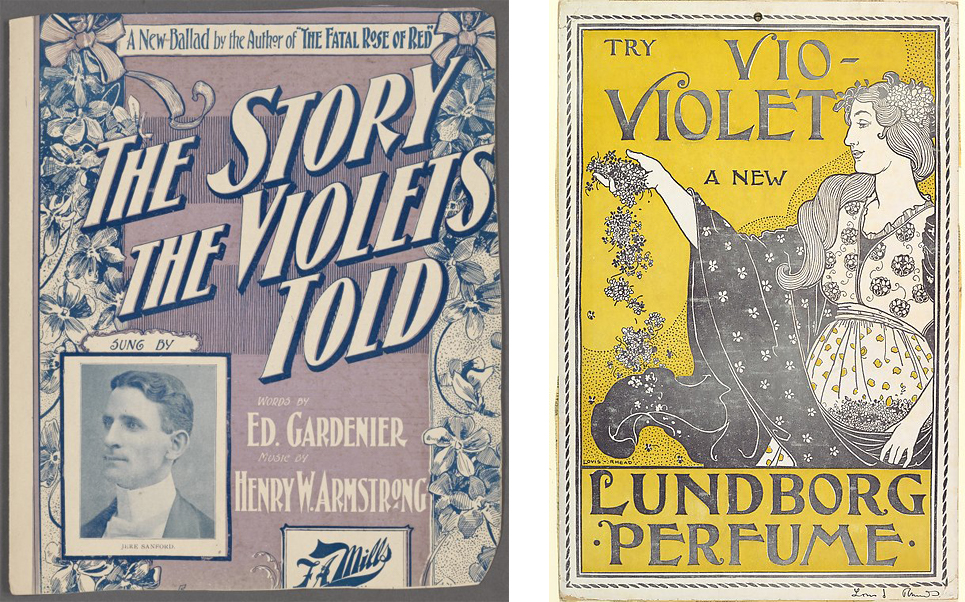

From left: New York Public Library / Metropolitan Museum of Art

Pure, unadulterated submissiveness isn’t the only “secret” of a flower like violet.

Rhyner notes that the language of flowers gained popularity in the Western world only after its introduction by German Orientalist Josepher Hammer-Purcell. During a stay in Turkey, Hammer-Purcell had studied a precursor to the language, which had intimate ties to sélams, “a form of covert communication in which the exchange of symbolic objects, including but not limited to flowers, allowed cloistered harem girls to communicate with love interests outside of their walls.”

Women used them as a friendly game amongst other women, to entertain themselves, and as a way to communicate queer desire.

I think that connotation is more fascinating than any other bullshit meaning. Of flowers — and violet in particular – as a diminuitive yet powerful symbol of non-heteronormative love.

Further Reading

Chestnut School of Herbal Medicine

The Friends of the Wildflower Garden

The Last Stand: Napoleon’s 100 Days in 100 Objects

The Tate Museum

Flowers of Rhetoric

The Queerstory Files

The New York Times

Smithsonian Gardens

Hyperallergic

The New Yorker